My brother-in-law lives in Orlando, FL. During the fast approach of Hurricane Hilary, he was eager to help us prepare. After all, he’s got a lot of experience, living in Florida. He was also keen to remind us that they haven’t even had a significant hurricane yet. How could the first hurricane in the family be in California?! Hilary, thankfully, has passed. And every day we learn more about the costs and impacts of this unusual storm. How do we plan for a future where more frequent and more intense storms are more probable? Let’s explore the geography of our valley and what makes it so vulnerable to flooding.

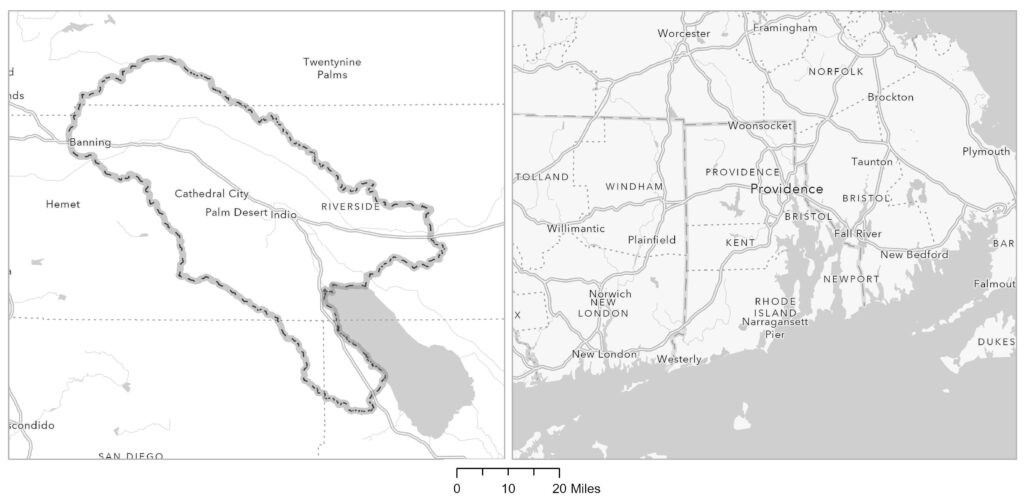

One of the compelling aspects of the Coachella Valley is its clearly defined shape. The ridges of our surrounding mountains and foothills mark the boundary of the valley. This boundary is mirrored by the watershed (the area where all of the water that falls in it and drains out of it goes to a common outlet) of the Whitewater River, the valley’s main watercourse, flowing from below San Gorgonio mountain to the northwest and draining to the southeast into the Salton Sea.

Draining down these mountains and foothills are myriad rills, gullies, creeks, and streams. Many run dry before they even join the Whitewater River, and most are seasonal at best. But during a large rainstorm, they come alive. Our basin is essentially a bathtub with high sides, draining out to the Salton Sea. And that’s why storms centered over the valley are so consequential.

Almost 35% of the nearly 2,150 miles (that’s the equivalent of the distance of a flight from Palm Springs to Philadelphia) of rills to steams have had their natural courses modified. Straightening, reinforcing, or redirecting these watercourses changes the natural drainage of the valley.

The Whitewater watershed has an area of 2,015 square miles. That’s halfway between the area of Rhode Island and the area of Delaware. That’s a lot of space to drain. A 2″ rainstorm in such an area amounts to 9.4 billion cubic feet of water or 70 billion gallons. If the average American uses 100 gallons of water a day, that’s enough daily water for 700 million people or nearly twice the US population.

Here in orange is the boundary we usually use at CVEP to aggregate data. It’s basically formed by the surrounding ridgelines and cut off at the boundary of San Bernardino and Imperial/San Diego counties. Perhaps we should expand this boundary a bit to take in the natural border of the Whitewater River watershed.